a pretty punchy move

Hope all is well in your neck of the woods. Here are two of the stories that caught my attention this week.

biden administration bans kolomoisky

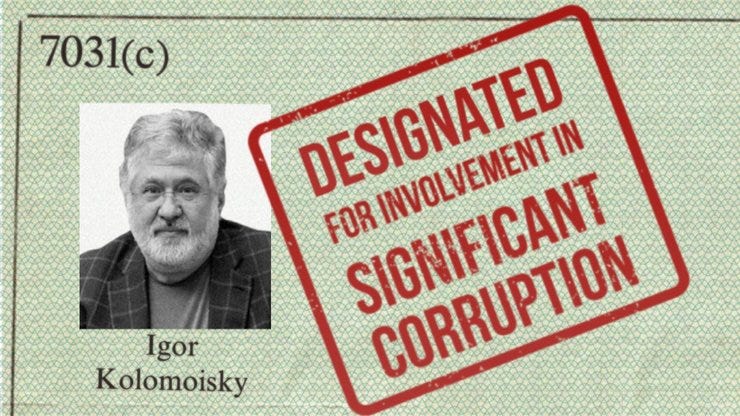

State Department graphic announcing the designation against Ukrainian oligarch Ihor Kolomoisky.

This morning, the State Department announced that it was barring Ukrainian oligarch Ihor Kolomoisky and his immediate family from entering the United States. This “7031(c) Designation” allows the Secretary of State to enact such a ban if an individual has been involved with “significant corruption.” This is a pretty punchy move for US policy towards Ukraine and the broader post-Soviet region.

Casual politicos may recall Kolomoisky’s name from the first Trump impeachment investigation, when diplomats and national security officials repeatedly mentioned his close relationship with President Volodymyr Zelensky. They characterized his widespread corrupting influence in Ukraine as one of the country’s biggest barriers on the road to democratic development. In August 2020, the Justice Department alleged Kolomoisky stole “billions of dollars from a bank he once owned, then us[ed] a vast array of companies to launder that money in the United States and all over the world.” The Ukrainian government nationalized and bailed out that bank, PrivatBank, in late 2016. As Zelensky assumed the presidency, all eyes were on his relationship with Kolomoisky; would Zelensky return PrivatBank to the oligarch? What kind of sway did Kolomoisky have over the president?

Zelensky has walked a mostly careful line with Kolomoisky; PrivatBank has not been returned to him, and the president has generally attempted to distance himself from the man whose TV station propelled his rise to stardom. But the State Department’s ban of Kolomoisky from US soil tells us a few things. First, though the Biden administration has been somewhat quiet on Ukraine to this point, they are serious about fighting corruption there (and not just full of hot air about it as the Trump administration was, using of Ukrainian corruption as a domestic political football). As the US Helsinki Commission’s Paul Massaro points out:

“The 7031(c) public visa ban can function almost exactly like an economic sanction since it is picked up by Politically Exposed Persons compliance databases like World Check that banks and others use to decide whether to do business. Kolomoisky is in for a world of hurt.”

Second, this is a loud and clear signal to Zelensky about the new administration’s stance on Kolomoisky and others of his ilk: they are an impediment to Ukraine’s democratic development. Their continued influence will cause problems in US-Ukraine relations, not to mention economic and military aid. And finally, the move has implications beyond Ukraine. It should put other oligarchs in the region on notice that their corruption has consequences, not only for their business interests, but for the lavish lifestyles and foreign perks that their families enjoy.

With the Biden administration promising more sanctions targeting the region, I’d be pretty nervous if I were a post-Soviet oligarch right now.

russsia trolls navalny supporters

Facebook released its monthly Coordinated Inauthentic Behavior report this week. In addition to networks in Iran, Thailand and Morocco, the social media giant removed a group of accounts likely associated with the Russian government targeting not foreign adversaries, but domestic activists supporting Russian dissident Alexey Navalny.

Unlike older Russian operations aimed at the United States or Ukraine, or even this fall’s PeaceData operation ahead of the US election, this campaign did not employ curated, mostly believable fake profiles; instead, it appears the Russian hucksters bulk-purchased 530 Instagram accounts to engage in hashtag- and location-squatting. Essentially, by flooding a hashtag or location tag with unrelated or negative content, the fake accounts attempted to dilute the messaging and coordination surrounding the January protests in Russia in support of Navalny, ultimately with the aim of undermining the movement and discouraging citizens from participating in it.

The Kremlin’s increasing use of cheap, bumbling means of influence tracks with my own observations over the past few years. As social media companies have gotten better at detecting cut-and-dry fake accounts, it has become harder for disinformers to create the networks they used to, so they are turning to the disinformation equivalent of brute force. Ukraine, for example, has seen the rise of in-country bot farms tied to the Russian government. For this newsletter, I covered a cash-for-comments scheme I identified that pushed pro-Russian rhetoric about Crimea just before the US election. These campaigns are extraordinarily cheap, so there is not much reason for Russia to stop. Even if they don’t generate much engagement, they do pad Russia’s image as a big, mean, cyberbully, and that’s even more powerful than driving discord or keeping protestors off the streets.

Mark your calendars: next Friday I’m moderating an online discussion on countering disinformation and freedom of expression in Ukraine. Join me and three fascinating Ukrainian experts at 10am ET.