Foreign correspondent Sabra Ayres left Moscow in March, but Russia wasn’t done with her yet.

In late October, an Instagram post of the sunset from her new apartment was flooded with comments about Crimea, the Ukrainian peninsula that Russia illegally annexed in February 2014. “The newly elected President of the United States must recognize Crimea!” one declared. “It was our legitimate decision in 2014 to come back home. Crimeans are Russians!” asserted another. Some discussed the looming presidential election: “You choose from two WHITE old men and lie to the world about the needs of people! Recognize Crimea as Russian!”

In total, Ayres — who was the LA Times’ Moscow correspondent for three years and often reported on Ukraine, having served as a Peace Corps volunteer there in the 1990s — was spammed with 325 such Russian propaganda messages. They were part of a cash-for-comments scheme consisting of at least 2500 accounts and 7800 comments across the photo sharing platform. Days before the contested November 3 election, they targeted public figures as disparate as Ayres, Beyoncé, Reese Witherspoon, and LeBron James.

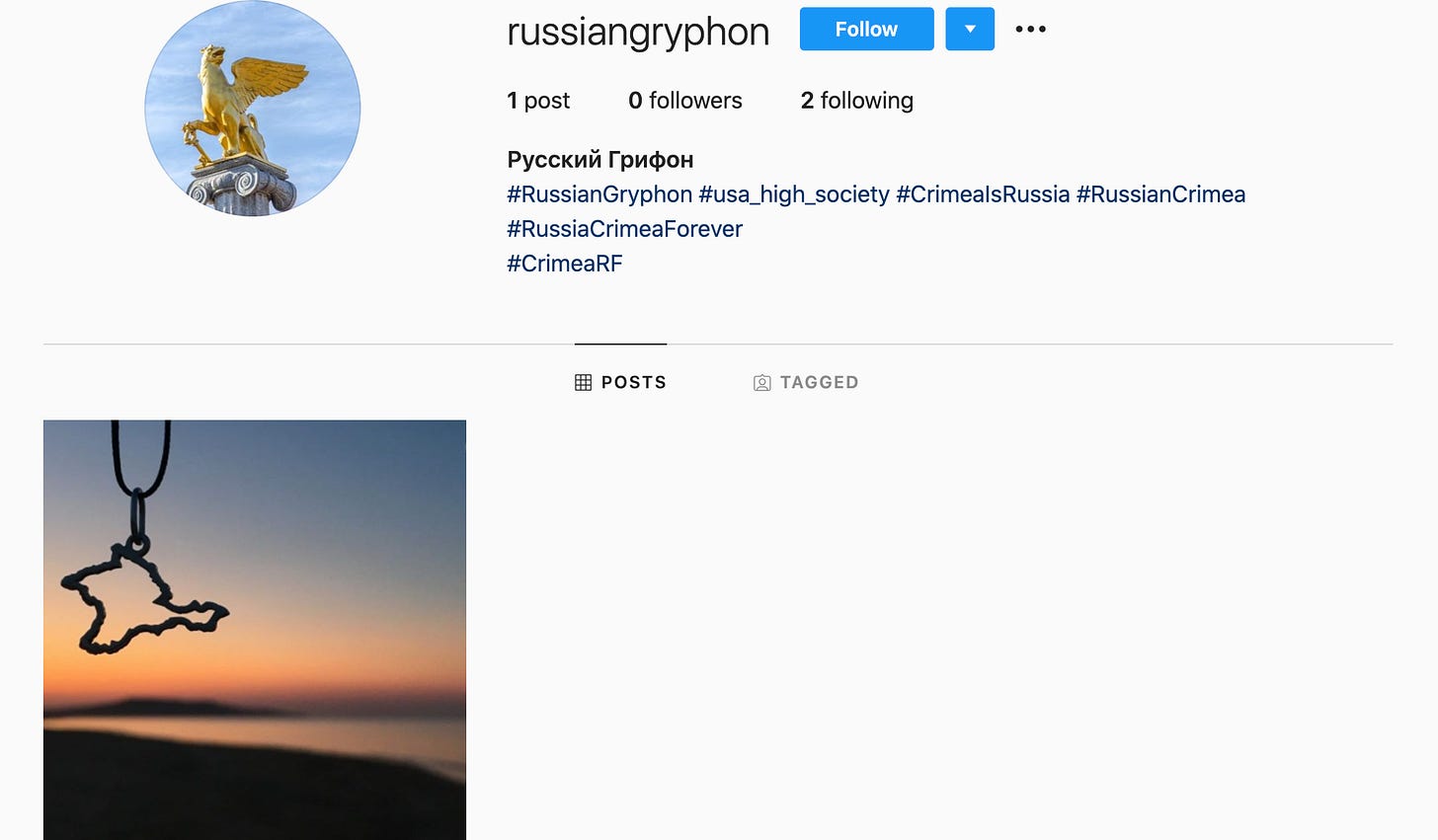

The operation called itself “Russian Gryphon” in a nod to Crimea’s coat-of-arms. But unlike mythology’s half-lion, half-eagle, this attempt at online influence was not awe-inducing in the slightest.

—

Ayres and I have been friends since we met in Ukraine in 2017, when we figured out we shared an affinity for cocktails and dogs and no tolerance for misogyny. When Ayres encounters Weird Internet Things she sends them to me, her resident Millennial Disinformation Expert.

“Holy shit,” she messaged me on WhatsApp on October 28, linking me to her sunset Instagram photo, which I had seen a few weeks earlier. “Look how the trolls went after me in this post.”

It was odd, but not unimaginable that pro-Russian accounts would target Ayres. Russia had violated Ukraine’s sovereignty and the rules-based international order in March 2014, seizing the Crimean peninsula first with force and later through a sham referendum, the results of which only 17 countries recognized. Since then, attempts to legitimize the referendum have been a mainstay of Russian disinformation efforts. Ayres most recently reported from Crimea in late 2018, filing a critical story on Putin’s unkept promises to the peninsula.

I scrolled through the comments, wondering why accounts from Russia, Iran, Central Asia, and a few countries in Latin America chose to target this post five days before the US Presidential Election. Ayres wanted to delete the comments; I asked her to leave them up “for science,” (also known as this newsletter).

I started by collecting all the comments on the post, including the comment text, username, and the time each comment was posted. Clicking through the profiles at random, I found many accounts that appeared to be inauthentic, with a high number of posts and little engagement over a relatively short period of time, like this aspiring influencer:

Beyond dunking on individual profiles, however, open source research on Instagram is challenging; while the platform’s endemic search function will happily help users locate pictures of cats, or workout videos, or top-notch brutalist architecture photography, or whatever else their interest might be, it doesn’t allow them to find a specific account’s comments or likes across the platform. All users — and researchers — can see is what other users themselves have publicly shared on their profiles. That is: I couldn’t simply plop the comments from Ayres’ post into Instagram’s search bar and find out where else they were posted across the platform. But I could plop them into Google. So I copied and pasted each of the 59 unique blocks of text into the search engine and crossed my fingers that the Google Gods had trawled some other posts this operation hit.

Bingo. I texted Sabra: “You’re in good company. Reese Witherspoon also got spammed.”

“Weird,” she responded. “Maybe because we were both debutantes? :)”

Unsurprisingly, that theory did not hold up long. The more I searched, the bigger and more varied Sabra’s new club got. I found Alicia Keys and Eva Longoria were members. An Ina Garten post about butternut squash soup also got the Crimea treatment. So did posts from Beyoncé, George Takei, the Wall Street Journal, America Ferrara, Angela Bassett, Lebron James, Debra Messing, and five separate US State Department posts. By the time I finished scraping the comments from these 16 photos — none of which had anything to do with Crimea, Russia, or Ukraine — I was working with over 34,000 comments, over 22 percent of which were Crimea-related.

With this data in hand, I was able to pull the commenting accounts’ histories — their public posts on Instagram — using CrowdTangle. I handed this data over to Alexa Pavliuc, a specialist in network visualization. Her work showed evidence of likely inauthenticity as well as strong evidence of coordination.

First, let’s take a look at posts over time. This is the post history of all 2572 accounts from August 1 to November 2:

(Data from CrowdTangle, a public insights tool owned and operated by Facebook.)

As you can see, the accounts start aggressively posting new content as the campaign begins in late October. This corresponds with the accounts I looked at when I first discovered the campaign, like the “influencer” above, who began posting his artful selfies on October 21. My favorite account in the dataset, “little.little.fox,” awoke from its hibernation in the “fairytale forest” (or Волшебный Лес in Russian, where its photos are tagged) on October 29 to post two new tiny fox pics, along with the comment: “In Crimean Republic we all believe that new American president will be smart enough to listen to us and reconsider his decisions about our resolution to be part of Russian Federation!”

An account called “russiangryphon” made only one post on October 27: a pendant in the outline of the Crimean peninsula hanging over the background of a marine sunset. The caption is a mish mosh of many of the comments in the operate. Russian Gryphon was selective in building its network; it only followed The Rock and the official Instagram account and had no followers itself. Its lone post had no likes or engagement.

The posting behavior of some of these accounts was certainly strange, and the fact that 108 unique messages were copied and pasted across at least 16 uploads displayed clear evidence of coordination. But what would it look like if Alexa visualized it?

Here we see comments on all of the posts we scraped before this operation hit them, as the operation is ongoing, and as it ends. All of the pink lines emanating from the posts are individual authentic comments. Where a line connects two posts, a comment was made on both. Some of the posts have a few commenters in common, but given the diversity of the accounts targeted, it makes sense that Ina Garten and LeBron James might have entirely different sets of commenters. But introduce our 2,500+ “Crimean” trolls — the green lines — and things start to look pretty different. Sabra Ayres is suddenly connected to Reese Witherspoon by more than a debutante past, and even Ina and LeBron start to look like they might share a few friends.

So we have evidence of inauthentic activity and coordination, but where was it all coming from, and why were Iranians and Russians and Venezuelans all posting about Crimea? Who was fake, who was real, and what was motivating them? My attempts to turn up some sort of coordination on Russian language message boards yielded nothing. It was purely an accident that I discovered the trail of breadcrumbs that led to the kitchen of this scheme.

I was sorting and cleaning the data, making sure I hadn’t hoovered up any authentic comments, when I came across a post in a mix of English and Persian:

The Persian translated to:

Oops. Someone copied and pasted too much text, confirming that users from all over the world were being dispatched to post these pro-Russian comments on high-profile Instagram accounts. Further scanning led me to another copy-paste error, in which one user leaves behind an email address along with their message:

A search revealed Kudrik63 is the admin of a few Facebook and VK pages, none of which appear to be related to this operation at first glance. So I clicked on poster Elisa_Bella'13’s profile. There, she advertises a service called “GetLike,” on which users can “complete simple tasks, make money, and conveniently withdraw it.”

Ding ding ding! I created a dummy account on GetLike, and to my delight, the service was still soliciting “Crimean” comments on several posts, paying just over half a cent (.05 RUB) per comment. The text of one read “We are citizens of the Republic of Crimea! We are Russia! The Russian Gryphon is a public all-Crimean initiative whose goal is the recognition of the Crimean peninsula's territory as part of the Russian Federation by the United States, as determined by the national referendum on March 16, 2014.”

In total, the 7400 comments that I was able to find (of which there are undoubtedly more that Google did not trawl; here’s one example from an AP reporter that did not turn up in my searches) would have cost the campaign’s organizer fewer than five dollars. And to what end?* Perhaps if they had been posting about #StoptheSteal or something Americans cared about, such a campaign could have been more successful, or at least more difficult to detect. It’s not as if the illegal annexation of Crimea was an election issue. This example does highlight, however, the thin line between authentic and inauthentic behavior — some of the accounts involved appear to be real people simply looking for a few extra bucks — and how a savvier use of Russian Gryphon-like campaign might change users’ impression of the online conversation.

As it stands, the Russian Gryphon — which has not solicited any further comments since November 2, I’ve checked — was just a bumbling operation adding noise to the chaotic comments sections of celebrity profiles. Now, at least Sabra Ayres and Reese Witherspoon have one more thing in common. If that was the Russian Gryphon’s goal, it succeeded.

*Perhaps Facebook will be able to shed more light on the motivation or provenance of the operation; I sent them my dataset last week. A few of the accounts I was tracking have since been disabled. Elisa Bella and Little Little Fox still exist.

New-ish from me:

For Foreign Affairs: a counter-disinformation agenda for the Biden Administration.

For The Washington Post: disinformation — now a partisan problem — will persist after the dust settles this election season.

Testimony before the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence, discussing online disinformation and conspiracy theories.

How to Lose the Information War has been named by New Statesman as one of the best books of 2020. Get your copy —now 30% off in Bloomsbury’s holiday sale — for yourself or a discerning loved one :)