For a year, this newsletter has definitely been “the wiczipedia whenever I want,” rather than “the wiczipedia weekly.” Now that my book has been out in the world for six months, the Trump era (and the seemingly one-minute-long news cycle it engendered) is over, and I published several big pieces of research that kept me occupied for the past year, I am feeling a pull back to basics.

I started this newsletter in 2015, long before Substack existed. Back then, the wiczipedia weekly was a roundup of all things Central and Eastern Europe, Russia, and Eurasia, with a growing dose of disinformation analysis as the topic grew in importance. I sent out my missives every seven days while working as a strategic communciations adviser to the Ukrainian Foreign Ministry in 2016-2017 and continued when I came home to a Trumpian Washington. I headed back to Ukraine in 2019 to cover the country’s pivotal presidential election — the one that brought Volodymyr Zelensky, entertainer-cum-president of Trump quid pro quo fame — to power, and moved my analysis to Substack, before it became the cool new free speech battleground. As in the rest of my work, I’ve always hoped this space would be a place where experts and laymen alike might learn something, and where I can have fun, making jokes that serious publications would cut, and writing about the things that matter to me, whether an editor thinks they’re newsworthy or not.

I’ve recounted this origin story because in 2021, staring down the barrel of another six months in isolation with only three male animals (husband, dog, cat) to comfort me, levity — especially related to the serious and depressing topics of my now-nearly-inescapable work — feels important. Doing something because I feel like it — ideally something more productive and healthier than snarfing an entire box of Cheez-Its in one sitting — feels critical.

So here we are, back in business! Having fun! Let’s talk about jailed Russian dissidents! (Clearly, my idea of fun is different than most people’s.)

navalny is jailed; russia reacts

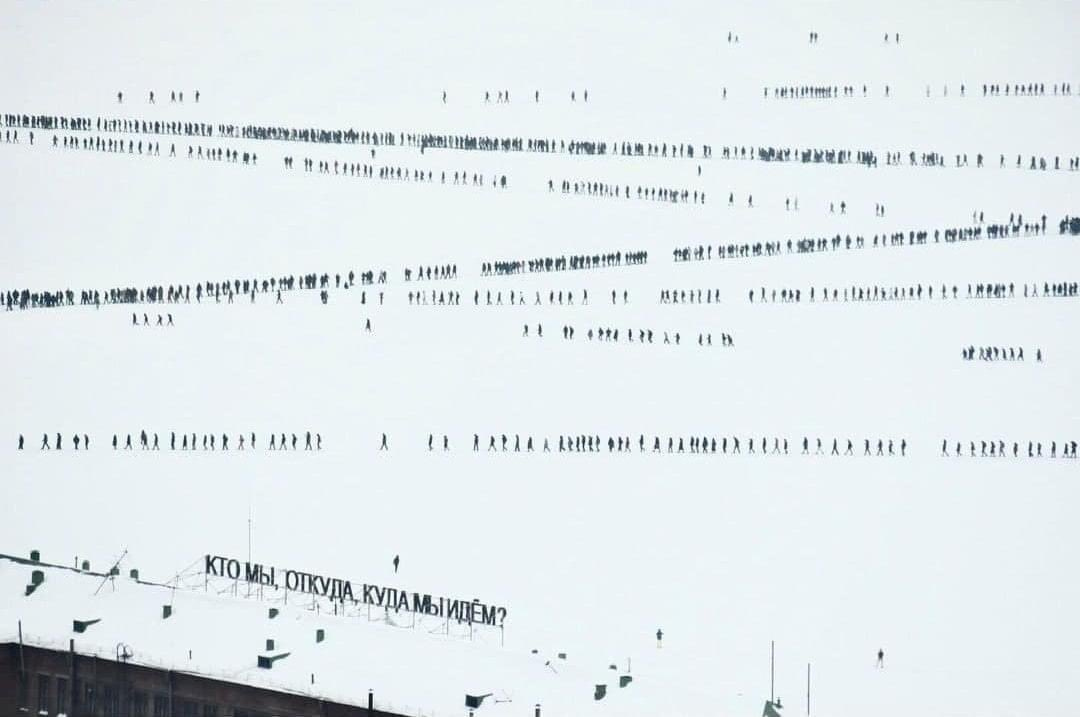

(Above: Pro-Navalny protesters in Yekaterinburg march on the frozen Iset River. Photo: @immortalpowny.)

I’ve been captivated with Russian TV the past few weekends. I watched as anti-corruption activist and dissident Aleksei Navalny flew home to Moscow from Germany, where he had been recovering after the Russian Federal Security Service tried to murder him by smearing Novichok, a military-grade nerve agent, in his underwear. Navalny was arrested at passport control, charged in a sham court hearing at a local police station, and this week, sentenced to two years and eight months in prison for violating the terms of his parole as he sought treatment for his Kremlin-ordered poisoning abroad. Today, he awaits a verdict in another sham trial; this one claims he defamed a war veteran while criticizing Russia’s recent constitutional referendum that handed Putin another 16 years in power.

Across the country, the Russians who have proteseted Navalny’s arrest and sentencing the past several weeks have been met with a forceful police presence that has arrested thousands, loaded them into paddy wagons, and handed out harsher-than-normal sentences for participation in the unsanctioned events. Independent journalists have been arrested and sentenced to weeks in jail for retweeting information about the gatherings. Commenting on the arrests in an emotional statement at his first trial earlier this week, Navalny said:

You can’t lock up millions and hundreds of thousands of people. I hope very much that people will increasingly realize this. And once they do — and such a moment will come — this whole thing will fall to pieces because you can’t lock up the whole country.

Three years ago, I partcipated in an international election monitoring mission that observed the 2018 Russian presidential contest. Navalny was barred from the ballot, but in one of the precincts we visited — in Bol’shaya Ryazan’, population 924 — a voter had scrawled “Navalny” on the inside of the voting booth. It was a single, poignant data point, but wasn’t a sign of a sea change. Even this week, after dominating headlines and garnering over 100 million views on his latest corruption investigation into Putin’s massive, secret palace, Navalny is still far from having the widespread support he yearned for in his statement this week. A recent Levada Center poll finds only 19% of Russians approve of Navalny’s activities, while 56% disapprove. The end of the Putin era is not imminent. But his team is focusing on the long game: Navalny enjoys higher support among 18-24 year olds (36%), which might buoy his movement ahead of parliamentary elections in the spring.

ukraine bans mainstream russian disinformation

Ukraine’s National Security and Defense Council banned three pro-Russian television channels and sanctioned their Ukrainian owner this week. The move was a surprising about-face from President Zelenskiy, who often spoke about reversing Poroshenko-era bans on Russian social media networks and websites deemed “national security threats” during his presidential campaign. In those days, it seemed to be one of the only concrete policy positions he had.

No longer. “About yesterday’s sanctions,” wrote Zelenskiy in the caption of a roguish Instagram photo featuring him in a bulletproof vest, “Now I hope that fakes and hybrid propaganda will truly decrease.” The US Embassy tweeted their support of the measure:

The US supports 🇺🇦 efforts yesterday to counter Russia’s malign influence, in line with 🇺🇦 law, in defense of its sovereignty & territorial integrity. We must all work together to prevent disinformation from being deployed as a weapon in an info war against sovereign states.

Meanwhile, EU High Representative Josep Borrell said:

While Ukraine's efforts to protect its territorial integrity and national security, as well as to defend itself from information manipulation are legitimate, in particular given the scale of disinformation campaigns affecting Ukraine including from abroad, this should not come at the expense of freedom of media and must be done in full respect of fundamental rights and freedoms and following international standards.

It’s a difficult situation; on one hand, Ukrainians have been clamoring for this move for years. Given that most Ukrainians — 74% in 2018 — get their news from TV, popular channels that legitimize pro-Russian narratives certainly contribute to the laundering of Russian disinformation in Ukraine. Even in 2019, as I covered the presidential election for the Pulitzer Center, most Ukrainians I interviewed recognized the insidiousness of domestic disinformation, and even demanded these very channels to be shuttered. But disinformation was not only broadcast on pro-Russian airwaves; the Poroshenko and Zelenskiy campaigns were engaged in a tit-for-tat disinformation campaign. As I reported, a Poroshenko adviser even advocated for shutting down the network that was supporting Zelenskiy, and the Ukrainian government endorsed restrictions on speech in favor of national and informational security. “What use is democracy…if a commitment to freedom of speech is used to defend lies?” they asked.

Zelenskiy and his advisers appear to have reached a similar conclusion, but, as under the Poroshenko administration, the context is worrying. Though Zelenskiy’s campaign was shockingly accessible to journalists, after assuming office the team and the president himself quickly shifted to an adversarial, highly-managed relationship with the press. Early last year, his Culture Minister was drafting regulations on countering disinformation and restricting press access that could have further politicized the information environment. (They were tabled as the coronavirus took hold.) And now, far from his original position of re-opening Ukraine’s information environment, Zelenskiy is banning outlets with the stroke of a pen. While in this particular case I understand the rationale, I do hope that Zelenskiy’s antagonistic relationship with other outlets does not color future executive actions.

In case you missed my latest publications:

Reckoning with the role of disinformation in the Capitol Insurrection, for Foreign Affairs: “The Day The Internet Came For Them”

Investigating the use of gendered and sexualized disinformation against women in public life: “Malign Creativity: How Gender, Sex, and Lies are Weaponized Against Women Online”

The precis of #MalignCreativity, explaining gendered attacked against women politicians and reflecting on my own experiences with gendered online abuse, for WIRED: “Online Harassment Toward Women Is Getting Even More Insidious”

Thanks for reading. See you next week!